The Ukrainian President is visiting Saudi Arabia for the first time in May 2023.

The war in Ukraine has underscored critical lessons for armed forces worldwide—lessons especially relevant for Arab militaries that rely heavily on foreign partners for their defense capabilities. Three core areas stand out: alliances and dependency, training and leadership culture, and procurement strategies.

Alliances and Dependency

Several Arab countries—most notably the Gulf states—have signed defense agreements with the United States, while Egypt and Qatar enjoy the U.S. “Major Non-NATO Ally” designation. These partnerships provide significant advantages, but over-dependence on a single partner carries strategic risks. Relying on one supplier creates a monopoly that can restrict access to advanced weapons and delay adaptation to emerging threats. It also grants the supplier political leverage, as control over spare parts, ammunition, and modernization cycles can be used to influence national decision-making. Moreover, even neutral suppliers may prioritize their own needs or those of their closest allies during times of crisis, delaying deliveries to others.

To address these vulnerabilities, Arab states must pursue diversification—both militarily and politically. Establishing partnerships with both Eastern and Western powers enhances strategic autonomy and broadens access to technological solutions. Such partnerships should meet two key conditions: they must be strategically aligned, serving vital defense interests for both sides, and they should be built on a shared scientific base that promotes joint research and development. This approach allows knowledge integration into indigenous production, reducing reliance on imports.

Wealthier Arab states, especially those in the Gulf, could collaborate with more populous countries such as Egypt to build a robust scientific-industrial defense foundation. Civilian technology firms should lead innovation efforts within realistic, long-term frameworks, focusing on fields like telecommunications, electronics, computer science, and mechatronics. Partnerships with technologically advanced and defense-innovative nations such as South Korea and Turkey can accelerate knowledge transfer and industrial localization.

Balancing relations with global powers is equally important. Arab states should maintain ties with the United States, China, and Russia, diversifying arms sources while avoiding excessive alignment with any single bloc. Although the United States remains the most consistent partner for both powerful and less militarily capable Arab states, diversification provides a hedge against global political shifts. However, the U.S. maintains five key strategic objectives in the Middle East: protecting shipping lanes, ensuring energy security, confronting competitors and adversaries, combating terrorism, and maintaining a strategic balance in the region while guaranteeing Israel’s ability to defend itself. In this context, Prime Minister Netanyahu’s security policies appear to conflict with Washington’s fifth objective, as his agenda seeks to alter the balance of power and grant Israel a monopoly on regional influence. This creates a challenge for Arab states striving to strengthen their military capabilities and diversify their weapons sources, even amid peace agreements and the Abraham Accords.

Training and Leadership Culture

Many Arab militaries still operate under centralized command systems that stifle initiative and slow response times—an approach ill-suited to modern warfare. In an era dominated by drones, cyber operations, and electronic warfare, speed and flexibility are crucial. Rigid hierarchies struggle to adapt to the fluidity of multi-domain battlefields.

Decentralized leadership cannot be cultivated through military training alone; it must also reflect societal values that encourage independent thinking. However, armed forces can foster this mindset through realistic, adaptive training grounded in modern battlefield developments. The Ukrainian experience highlights several valuable lessons. Officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) must be trained to understand the commander’s intent and adapt tactics independently rather than waiting for explicit instructions. Junior leaders should be educated to think strategically, not merely execute orders. Expanding participation in joint exercises with advanced militaries helps absorb best practices and operational concepts, while updating military education to reflect NATO-style methodologies—tailored to Arab realities—ensures relevance.

Furthermore, combat units would benefit from basic STEM education, enabling soldiers to understand and exploit battlefield technologies. Select officers and NCOs should pursue dual academic paths that combine military, social, and technical studies. Finally, realistic live-fire drills and simulations are essential to prepare troops for the complexities of urban, hybrid, and multi-domain warfare. Through these reforms, Arab militaries can produce adaptable, well-educated leaders capable of operating effectively in high-tempo combat environments.

Procurement Strategies

Modern weapons systems often rely on components sourced from multiple countries, creating vulnerabilities when suppliers impose political or logistical restrictions. To mitigate this risk, Arab states should focus on localizing production, starting with spare parts and non-technological components. Joint manufacturing with multiple international partners can distribute risk, enhance technical know-how, and improve resilience under political pressure.

A shift in procurement philosophy is also needed. Historically, many Arab countries have favored high-profile, prestigious weapon purchases over systems that are maintainable and adaptable for prolonged conflict. Experiences in Yemen and Libya have shown that dependency on foreign maintenance severely undermines combat readiness. The war in Ukraine reinforces the importance of investing in systems that can be repaired, upgraded, and sustained locally. Maintenance must be viewed as a strategic priority, not an afterthought.

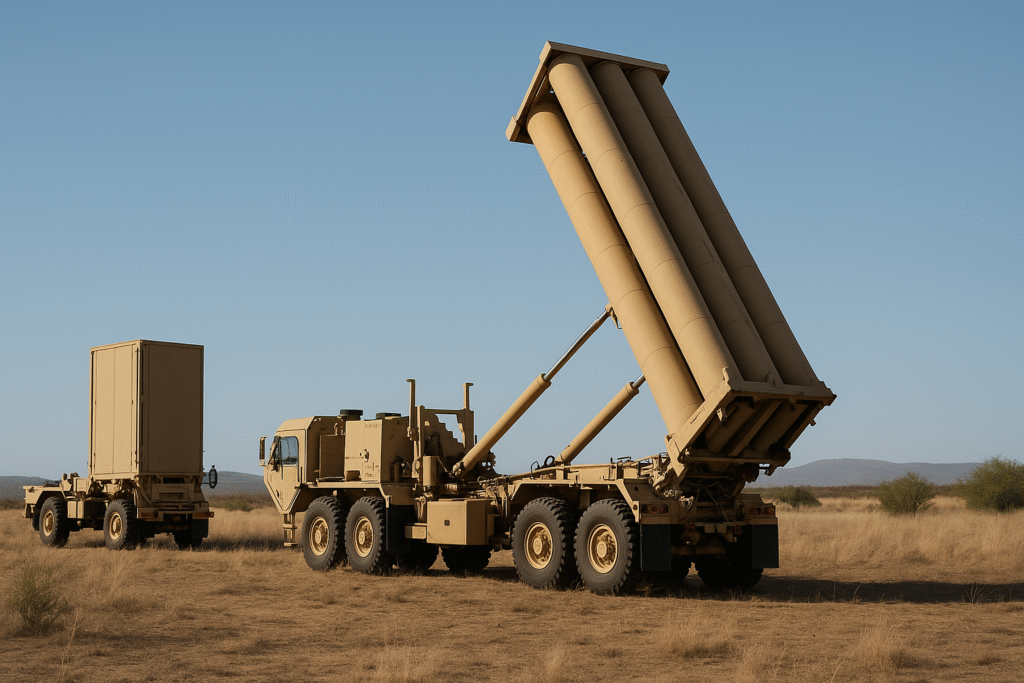

Arab militaries should also prioritize cost-effective, asymmetric systems—such as drones, counter-drone technologies, and mobile air defense units—alongside traditional heavy platforms like fighter jets and tanks. Procurement decisions should be guided by operational needs and life-cycle costs, rather than political alliances or prestige.

Conclusion

The war in Ukraine offers three vital lessons for Arab armed forces. First, they must diversify alliances and build indigenous capabilities to avoid strategic dependency. Second, they must reform training and leadership development to produce flexible, innovative commanders who can operate under dynamic conditions. Third, they must rationalize procurement to ensure systems are sustainable, locally supportable, and operationally relevant.

By internalizing these lessons, Arab armies can strengthen their resilience, autonomy, and combat effectiveness in an increasingly unpredictable global security landscape. The goal is not to replicate Ukraine’s experience but to adapt its lessons to the Arab world’s distinct strategic, cultural, and economic realities.